Interactive programs

In this unit you will be learning how to create interactive programs, meaning programs that interact with the person that is running them. Any time you interact with a program, you need both input and output. Input means that you are providing data or commands to a program. You can provide input in many ways:

- typing on a laptop keyboard

- drawing on a tablet

- recording a podcast using a microphone

Photos by Everyday basics on Unsplash, Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash, and Christin Hume on Unsplash

When the program responds, it typically provides you with output, showing what it did for you. Following the examples above, this could be:

- putting the text you type into an email

- showing you a drawing based on the strokes you made

- showing a soundwave that contains your interview with a guest

Everything you do on your phone is a series of you providing input (by tapping or speaking) and the phone providing output (by displaying on the screen or talking back to you).

To keep things simple, we will start with programs that only use the keyboard for input and your screen for output.

As you go through this unit, create a folder in your cs110 project called

unit3. You can put all your programs there.

You can provide output for your program using the print() command. To use

print, you give it a string that you would like to print:

print('Hello world!')To see this in action, create a file in your unit3 project called

printing.py. Type in this program:

if __name__ == '__main__':

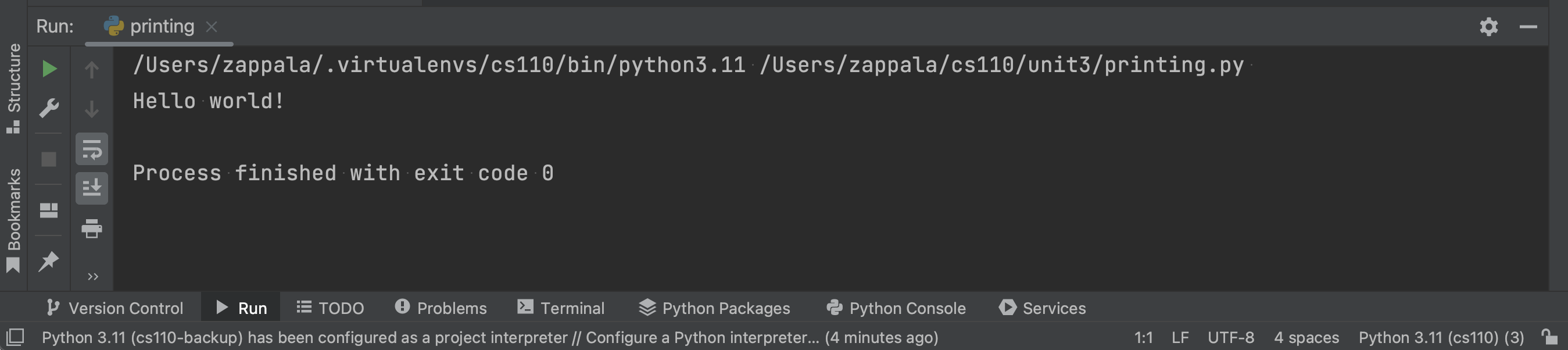

print("Hello world!")When you run this program, PyCharm will open a Window at the bottom to show you the output:

A few things to notice, from top top bottom:

-

First, the window shows you that PyCharm ran your program. In my case, it says it ran

python3.11on theprinting.pyprogram. Remember, every file in your file system has a path. In my case, the path topython3.11is/Users/zappala/.virtualenvs/cs110/bin/python3.11and the path toprinting.pyis/Users/zappala/cs110/unit3/printing.py -

Next, the window shows you Hello world!, the string that you asked it to print. Python has printed this to your screen.

-

Below that, the window shows Process finished with exit code 0, which is normal. This means your program finished without causing any errors. You will see errors here if your program doesn’t operate correctly.

-

There is a series of tabs at the bottom, and you are in the

Runtab. This is where Python will show you the output of running your program.

The print() command will actually allow you to give it multiple strings to

print. Modify your program so it reads:

if __name__ == '__main__':

print("Hello world!")

print("Hello", "world!")

print('Hello', 'world', 'out', 'there!')When you run this, it shows:

Hello world!

Hello world!

Hello world out there!-

The first line comes from

print("Hello world!"). Python prints out the string. -

The second line comes from

print("Hello", "world!"). Python prints out the first string, then a space, then the second string. -

The third line comes from

print('Hello', 'world', 'out', 'there!'). Python prints out all of the strings you provide, separated by spaces.

Input

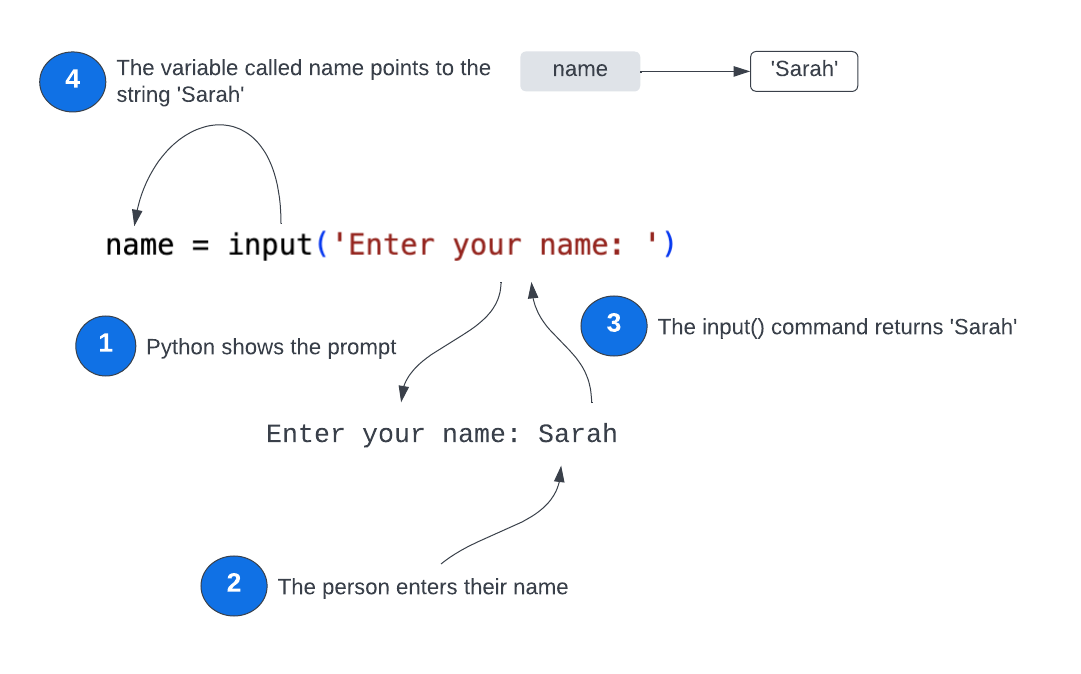

You can provide input to your program using the input() command. You provide

input with a string to use for a prompt:

name = input('Enter your name: ')Python will print this prompt on the screen and then wait for the person running

the program to type a response. When the person ends a line with the enter

key, then Python returns their response. In the line shown above, we store the

response in the variable called name.

To see this in action, create a file in your unit3 project called

inputting.py. Type in this program:

if __name__ == '__main__':

name = input('Enter your name: ')

print('Your name is', name)When you run this, it shows:

Enter your name:Type whatever name you want:

Enter your name: Kermit

Your name is KermitYou can see that the print() statement prints both Your name is and the name

that you type, which is stored in the variable called name.

Formatted strings

Often when we print strings, we want to print a variable mixed with other strings. When you print as above:

print('Your name is', name)you are somewhat limited in what you can do. A more powerful way to print is to use a formatted string:

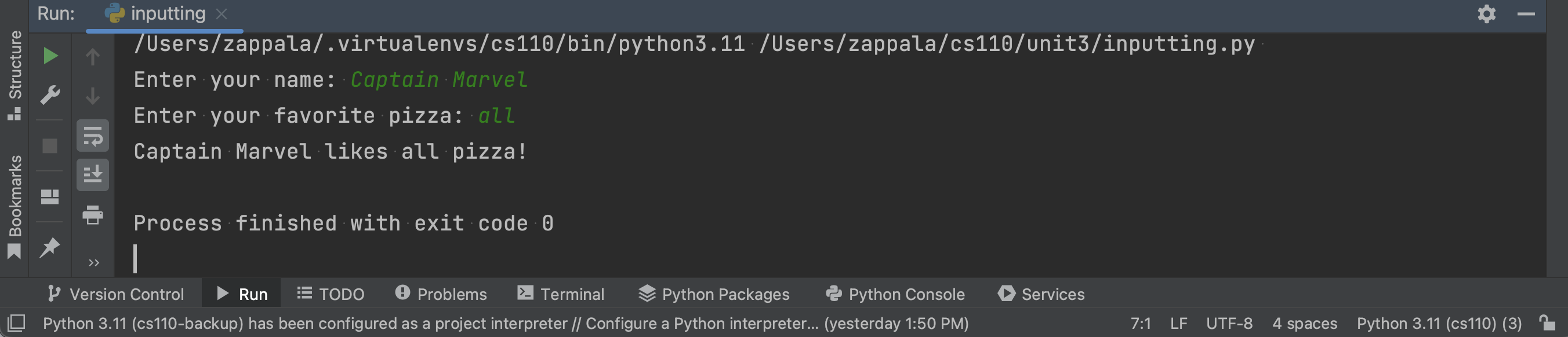

if __name__ == '__main__':

name = input('Enter your name: ')

pizza = input('Enter your favorite pizza: ')

message = f'{name} likes {pizza} pizza!'

print(message)A formatted string begins with f and then has a string in quotes. Inside the

string, you can use variables by putting them inside of curly brackets {}.

The above program will:

-

ask the person running the program to enter their name, and store their answer in the variable called

name -

ask the person to enter their favorite pizza, and store their answer in the variable called

pizza -

create a variable called

messagethat uses a formatted string, which contains<name> likes <pizza> pizza; this ends up containing something like ‘Kermit likes pepperoni pizza’ if the person types ‘Kermit’ and ‘pepperoni’ -

prints

message

You can see this in action by changing your program in inputting.py to include

the above code. Run it and you will see something like this:

Finally, you will notice we used a variable to hold the formatted string:

message = f'{name} likes {pizza} pizza!'

print(message)You don’t necessarily need a variable in this case. You could just write this code:

print(f'{name} likes {pizza} pizza!')We are just putting the formatted string directly into print(). This works

just as well!

Return

When using input() it is helpful to write small functions that call input()

and return the result. So let’s revisit return,

which we saw earlier in unit 2.

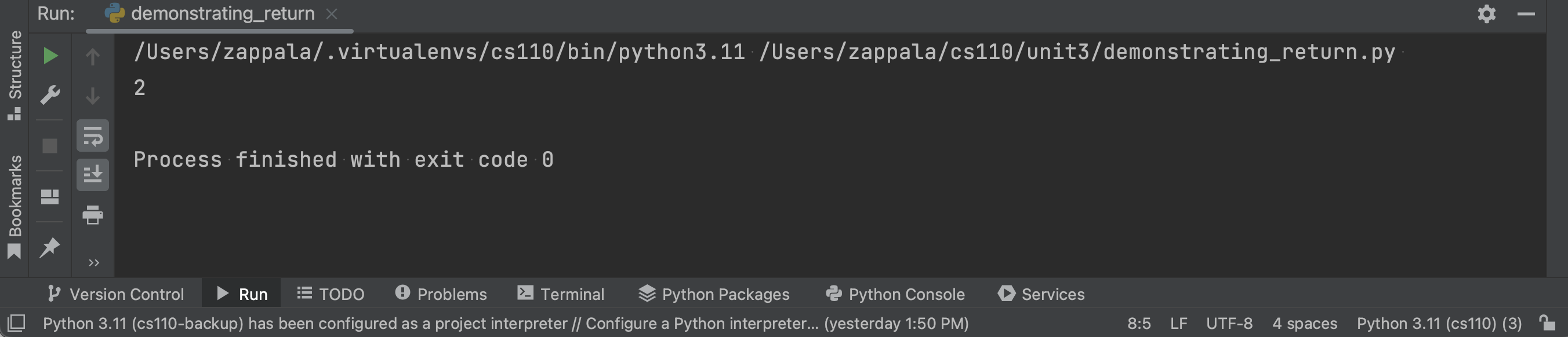

Take a look at this small program:

def give_me_two():

return 2

if __name__ == '__main__':

value = give_me_two()

print(value)-

Python will run the

main blockfirst. -

The first line inside the main block says store the return value of the

give_me_two()function in a variable calledvalue. -

At this point, Python will run the

give_me_two()function, which returns the value 2. -

Python will take this returned value,

2, and store it in the variable calledvalue. -

Python prints

2

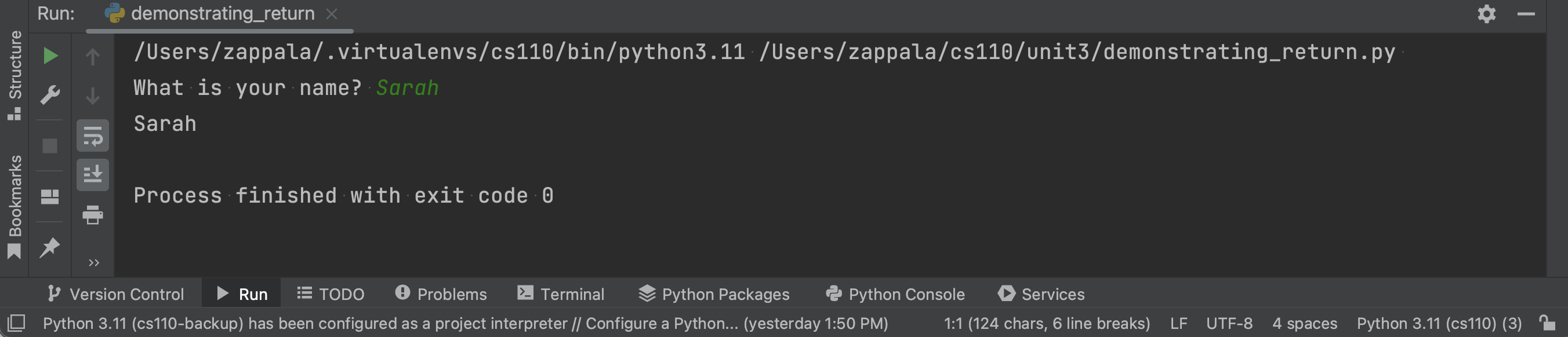

You can put this program in a file called demonstrating_return.py and run it:

Now replace this program with the following:

def get_name():

return input('What is your name? ')

if __name__ == '__main__':

value = get_name()

print(value)Notice that we have a very simple function, get_name() that just calls

input, gets what the person types, and then returns it. The main block calls

get_name() and prints value. Run this and you get:

Welcome to Wendy’s

OK, now that you understand print(), input(), formatted strings, and

return, you’re ready to write an interactive program. Write a program that:

-

Welcomes a person to Wendy’s:

Welcome to Wendy's! -

Asks for the person’s name:

What is your name? -

Prompts the person for a sandwich type:

What kind of sandwich do you want? -

Prompts the person for sandwich additions: “What do you want on it? `

-

Prints out an order for the staff:

<person> wants a <type> sandwich with <additions>!

See if you can write this program with a friend. We’ve given you everything in

this guide that you need for this task! Write your code in the unit3 folder,

in a file called wendys.py. Remember to use functions and return!

Here is one way to write this program:

def get_name():

return input("What is your name? ")

def get_sandwich():

return input("What kind of sandwich do you want? ")

def get_additions():

return input("What do you want on it? ")

def print_summary(name, sandwich, adds):

print(f"{name} wants a {sandwich} sandwich with {adds}!")

def main():

print("Welcome to Wendy's!")

name = get_name()

sandwich = get_sandwich()

adds = get_additions()

print_summary(name, sandwich, adds)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()You will notice:

-

This solution is broken down into a bunch of functions, many of which use the

returnstatement. -

One of the functions,

print_summary()takes three arguments — the name, the sandwich, and the additions, and then prints out a formatted string using these variables. You can write functions that take s many arguments as you want.